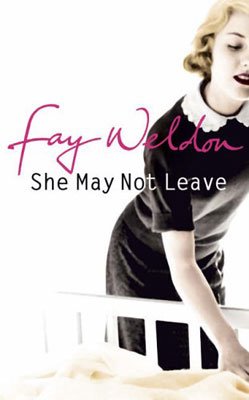

She May Not Leave, by Fay Weldon, published by Fourth Estate, $36.

She May Not Leave, by Fay Weldon, published by Fourth Estate, $36.From the book jacket:

Be careful who you invite into the bosom of your home - she may never leave... The new novel from Fay Weldon, the writer who knows women better than they know themselves. Hattie has a difficult loving partner, Martyn, an absentee mother, Lallie, and a cynical attentive grandmother Frances. She tries to do the right and moral thing in a tricky world, and always has. But she now has a baby, Kitty, which makes true morality rather harder to achieve. Somehow, money has to be earned. Into this household comes Agnieszka, from Poland, a domestic paragon. But is she friend or foe? And even if she is foe, and seems likely to bring the domestic world crashing down around their ears, can they afford to let her go? Well, no. Martyn works for a political magazine, Hattie for a literary agency. At work, too, integrity is suffering as the need for compromise becomes ever more pressing. And always in the background is Frances, tracing the family and social history: and not just family and society but the dwelling houses too; and all those girls and women (the au pairs, the child-minders, the cleaners) who've made Hattie what she is. Not to forget that hefty dollop of male genes which has also played its part - for Hattie's is a lively and none too respectable background - and now, finally, Agnieszka, come to claim her rightful heritage - which is, let's face it, everything. Will Hattie go to the wall? And poor little Kitty! Or will rescue come?

*

*A Testament to the One True Fay

By KNIGHT, Kim

Source: Sunday Star-Times

MEN ARE irrelevant, says Fay Weldon. Unless you want to be happy.

"You can have children without them, you don't have to be married, you

can earn a living... but I think it's a fairly miserable life for

women without men."

Weldon is the 74-year-old feminist author with more than 25 novels,

one Booker prize - and three husbands.

"I get really cross with women when they denigrate men, when they make

terribly funny sweeping statements about men."

She pauses. "Which is how I make my living!"

In her latest book, She May Not Leave, Martyn the man is trumped into

pseudo- motherhood and Hattie the wife gets her life back. Classic

Weldon.

"I think there are sets of pre- occupations," she says of her stories.

"One is our extraordinary propensity to deceive ourselves about what

we're doing. Self-deception and denial and how we all look after our

own interests while pretending that we're not - or how morality fails

in the face of necessity."

Lessons in morality from the woman whose characters specialise in

revenge? Careful what you tell Weldon over lunch.

"I said something terrible to a woman recently," she says.

"Unfortunately they'd all been drinking and I hadn't. She said she was

really upset about the orphans in Kashmir and couldn't we do anything?

I said, `well, no you can't, but you could actually ring up social

services and offer to foster a child around the corner'."

People don't want to hear that, Weldon acknowledges. "Because it

suggests they might actually have to take some action ... your heart

bleeds and so does mine, but I don't say so because I know the answer

is to bring some children into my house who could very well do with a

little bit of warmth and civilisation. I'm not prepared to do it."

But she might pray for them. Weldon - whose early church experiences

include singing hymns at Christchurch Girls' High School (she was

brought up in New Zealand, but returned to the UK as a teenager) - has

rediscovered religion.

"I don't go on about church, unless asked, but if people went to

church, they would get a shape to their life. I think it's extremely

difficult for people to live without some sort of faith or confidence

or sense of a morality. It's almost impossible for people to live

within any moral framework which is not related to a religion."

How does this woman's libber see God?

"I don't. I don't have the tools to do it. I have five senses, and

they're not enough. One just knows there is more... I get intimations

of it sometimes, you get an aesthetic appreciation of things and

intellectual pleasure in things sometimes which is sort of more than

human."

Through the church, says Weldon, "the wisdom of the ages is available

to you. And, absolutely, a sense of collectiveness. A small cluster of

people looking rather fearfully at the heavens wondering what's going

to happen next. It sort of focuses the mind. And you look after your

neighbour."

Dear reader, don't despair. Weldon's latest offering might be strong

on morals, but it also features group sex and drugs. "Why should what

you write in your 70s be any different to what you write when you're

in your 30s, except that you know more when you're 70? You know what's

going to happen next, you have seen it happen and this is a great

advantage. That I like. I don't like the fact that when I sneeze, I

worry in case I slip a disc."

Weldon is sharp and funny, even though it's after 11pm in Dorset. It's

not too late for an interview, says her husband, Nick Fox. They're

just home from dinner, he says, and Fay's on antibiotics for her

tooth, so she's had nothing to drink. And then she's on the phone,

alternately engaged and detached, depending on the topic. "Always

controversial," suggest the critics. "I really am impervious to

labels," retorts the real thing. "So if they choose to think that,

then that's all right."

Truth is, there's little to say about Weldon that she hasn't said

about herself. Her autobiography (Auto da Fay, 2002) takes the reader

to 1963, and her fiction snatches portions of her life, before and

since. The latest is heavy with references to New Zealand.

"It sort of pops up," she says of the country she remembers in

fragments ("Of Amberley, I remember the hot wind blowing off the

mountains, day after day, and a bare flat landscape and a lot of sheep

there was no escaping").

"Is Cranmer Square still full of slugs and snails when it rains?" she

asks, when I tell her I'm sitting a stone's throw from her old high

school.

New Zealand shaped her memories - but not her character.

"I don't think I have a character at all that you could lay a finger

on! It's sort of the New Zealand desire to be useful... your time

needs to be spent making things better, doing something, getting

something to happen..

"It's kind of a nuisance really, this tendency. You'd obviously live a

much easier life if you didn't feel that you had to be useful. You

could just be decorative, or do nothing. Be a burden to others."

No comments:

Post a Comment